Trigger Warning / Disclaimer

This story contains references to anxiety, panic attacks, and trauma following a violent incident. If you are struggling, please consider reaching out to a mental health professional—you are not alone.

Reader discretion is advised. If you find such themes triggering, please proceed with caution.

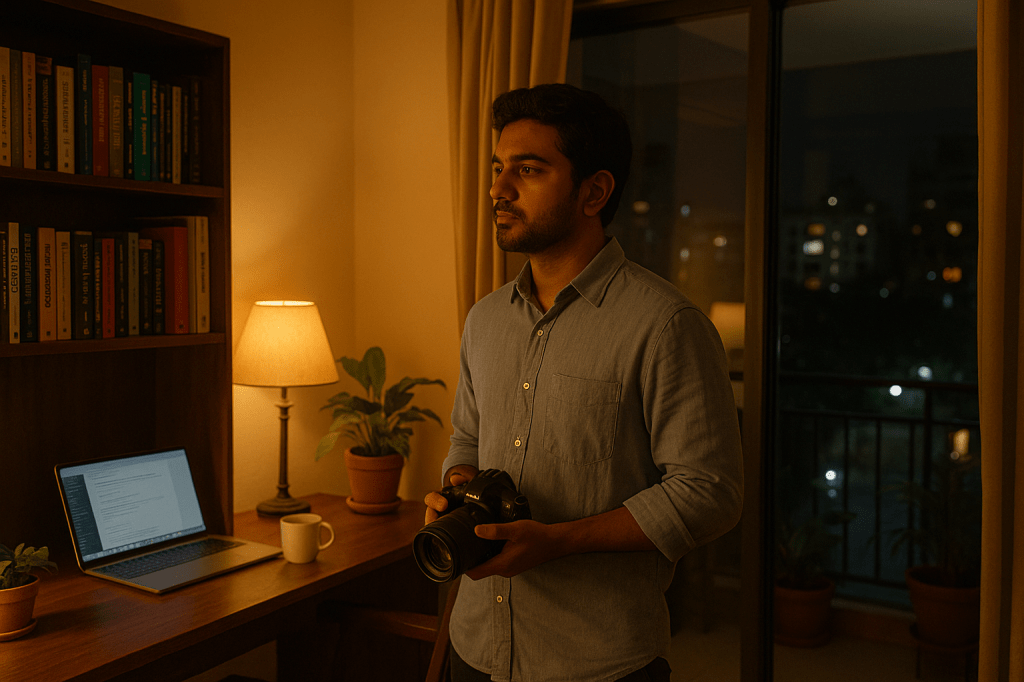

The lights flickered overhead as Aarav sat on the floor of his flat, his back pressed against the wall. The whirr of the ceiling fan was the only sound in the room. The world outside buzzed with life—honking cars, schoolchildren chattering, the distant clatter of train tracks—but it felt like a separate universe. Aarav hadn’t stepped out in over a month.

He once thrived in the city’s chaos—a product developer for a health-tech start-up, always on the move, always reachable. That was before the incident.

It happened on a humid August morning. Aarav had taken the 8:22 local from Dadar, earbuds in, mind already half at work. Somewhere between stations, a fight erupted near the door. A scuffle, shouts, and then—blood. A man was shoved off the train as it pulled out of the platform. Aarav saw the body fall. Heard the sound that still echoed in his head. And the worst part—he couldn’t move. He froze.

Since then, the station became a monster in his mind. His body shut down every time he even thought of leaving home. A dull panic settled in his chest and refused to leave.

“I’m broken,” he once whispered to the ceiling. “I’m twenty-nine and afraid of the footpath.”

—

His sister, Ira, showed up the day after he stopped responding to calls.

“Open the door, Aarav,” she called, knocking insistently. “I’m not going away. You know I’ll climb in through the kitchen window if I have to.”

Reluctantly, he opened it.

She stood there with a paper bag, her hair in a messy bun, wearing an old Kurti and sneakers. “I brought your favourite—the soggy rajma chawal from that dhaba you used to love.”

“I don’t need—”

“You need food, and you need people. You don’t have to pretend with me.”

He stepped aside. “The place is a mess.”

“I’ve seen worse. Remember your hostel room in college? That thing had a fungus ecosystem.”

She stayed that night, then the next. She didn’t nag or ask too many questions. She just worked quietly on her laptop beside him, played old Kishore Kumar songs, and made tea that didn’t taste like cardboard.

On the fourth evening, she asked gently, “Do you want to talk about it?”

He looked away. “Not really.”

“That’s okay,” she said, “We don’t have to talk. But can I ask something else?”

He nodded.

“What scares you more—the memory or the fact that you froze?”

He blinked. “Both.”

—

One night, Aarav woke up gasping. The dream was always the same—the man falling, his eyes wide, the rush of air, the sickening thud that never came but always lingered. The sound didn’t exist, but it haunted him like an unfinished sentence. Every night it ended the same way—with his hands clenched into fists, sweat coating his back, the echo of his own heartbeat thundering in his ears.

He stumbled to the balcony, barefoot. The tiles were cool under his feet, grounding. The city below didn’t care. A paani puri vendor packed up his cart, scraping metal lids with tired rhythm. A couple argued softly near a parked scooter. A cat jumped onto a tin roof and startled a pigeon into flight.

Life moved on.

But inside Aarav, time still stood still at that one moment—on that train, at that platform.

His palms pressed to the balcony grill. He stared into the streetlamp’s glow, almost punishing himself to stay present, to not look away. He wanted to scream. But instead, he whispered:

“I need help.”

The words felt like a betrayal of his own pride… but also like a lifeline tossed into his chest.

The next morning at breakfast, he stirred his tea with quiet purpose. Ira sat cross-legged on the floor, sorting through old family albums she had dug up for no reason other than to make the silence feel warmer.

“Ira…” he said, and she looked up, instantly alert.

“I think I need help.”

She didn’t smile triumphantly. She didn’t say, I told you so. She just touched his hand gently and said, “Then let’s find someone good.”

She paused, letting him breathe into the moment. Then softly added, “And I’m proud of you, Aarav. It takes strength to say that. Real strength.”

He blinked fast and looked away.

Later that day, as the sun filtered through dusty curtains, they sat side-by-side, scrolling through therapy listings. Aarav read profiles like a man skimming through memories he hadn’t made yet.

“I don’t want anyone who’ll just throw jargon at me,” he muttered.

Ira clicked open a new tab. “Okay, how about this one? Dr. Raina—she’s trauma-informed, works with young professionals, does cognitive work and somatic therapy both.”

He glanced at the picture. The woman in the photo looked calm. Real. Like someone who would see him, not just a case file.

“Let’s try,” he said quietly.

For the first time in weeks, the air in the room didn’t feel so tight.

—

They met Dr. Raina online. She had kind eyes and didn’t speak in riddles. She didn’t interrupt. She didn’t rush. Just held space like someone holding out an umbrella in the rain.

“You’ve experienced trauma,” she said in their second session. “And your mind’s doing its job—trying to keep you safe. But it’s gone into overdrive.”

Aarav frowned. “So I’m not weak?”

“No,” she said gently. “You’re scared. There’s a difference.”

That one sentence softened something inside him. A knot he hadn’t even known was there.

Week by week, they worked. Slowly. Breathing exercises that felt silly at first, but became rituals. Naming the panic when it came—giving it shape so it could shrink. Creating mental anchors—a wristband, a song, a pebble in his pocket—to remind him he was safe now. Not running from the memory, but not letting it rule him either.

Some days, therapy felt like dragging his feet through mud. Other days, it felt like standing in sunlight after a storm. But it was movement. It was life.

Ira helped with the exposure work.

One day, they simply stood outside the apartment door for three minutes. Another day, she took him to the parking lot at midnight, sat on the hood of the car, and said nothing. Just breathed with him.

“It doesn’t matter how small the step is,” she whispered, “as long as it’s forward.”

Some evenings, they talked about everything and nothing. Childhood fights. Their father’s weird tea obsession. The monsoon holidays in Goa.

Some evenings, they said nothing at all.

But one Thursday, Aarav lingered at the cupboard longer than usual. He pulled out a cloth-wrapped box and dusted it gently.

His old DSLR.

“Ira…” he began, his voice unsure, “do you think I could… take photos again?”

Her face lit up. “You should! Remember how you used to stop the car just to take pictures of clouds?”

He smiled faintly. “I still see them. I just… haven’t held the camera.”

That weekend, she arranged a photo walk on their building terrace. No pressure. No people. Just her, Aarav, a couple of planters, and the sky.

“Shoot the gulmohar,” she said, pointing to a blooming branch. “Pretend it’s a mountain.”

He raised the camera. It felt heavy. Not physically, but emotionally. Like memory and hope wrapped in black metal. He focused, adjusted, and clicked.

And clicked again.

The third time, he laughed. A real laugh. Not polite or forced.

Ira joined in, pretending to pose like a fashion model next to the potted basil. “Caption this: woman crushed under her brother’s artistic genius.”

He shook his head, but the grin didn’t leave his face. “You’re impossible.”

“And you’re back,” she said softly.

—

That night, Aarav uploaded the photos to his laptop. The gulmohar looked vivid. The shadows stretched across the floor like poetry. The clouds were soft. Still moving, still changing. Like him.

The fear didn’t vanish overnight. The panic still visited sometimes—at the sound of a sudden whistle, or a packed crowd on the news. But now, Aarav knew what to do. How to breathe through it. How to ground himself.

And more importantly, he wasn’t doing it alone.

One afternoon, as Ira stirred dal in the kitchen, he called out, “Hey… want to go down to the station with me this weekend? Just for five minutes. No trains. Just standing on the platform.”

She turned off the gas. “Are you sure?”

“No. But I want to try.”

She nodded. “Then I’ll be there. Camera and all.”

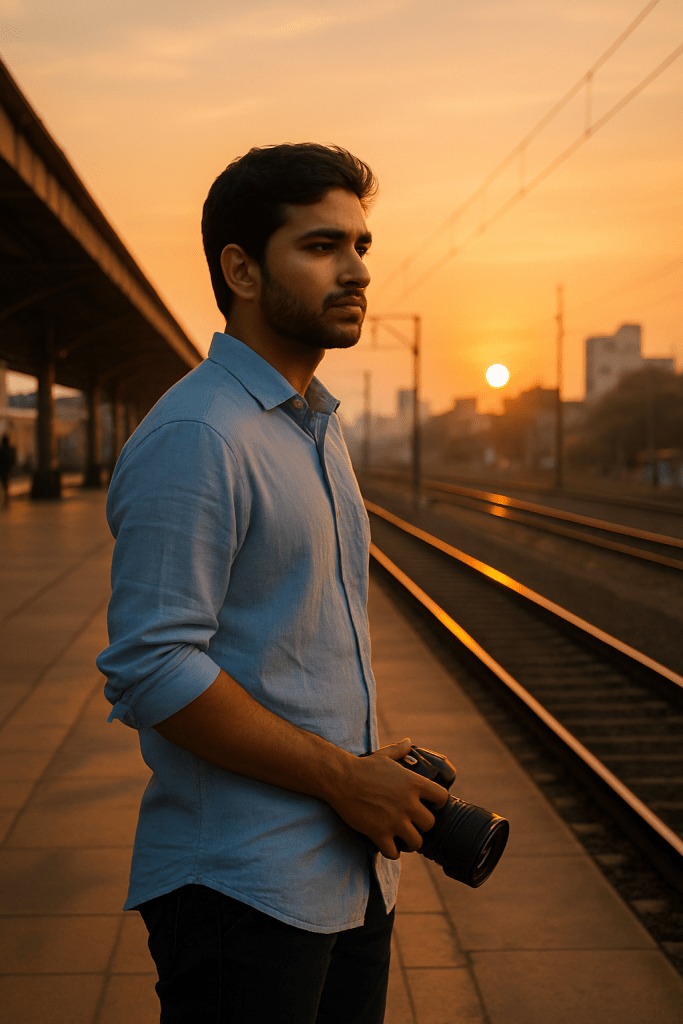

That Sunday, they took an auto to the Dadar overbridge at noon—less crowded, less chaos. Aarav’s breath quickened as they neared. His legs went cold. But Ira held his hand and said, “You’re not alone. Just stand. Don’t push.”

They stood near the footbridge. Trains came and went. People brushed past. A whistle blew.

He didn’t faint. He didn’t run.

He cried.

Not from fear—but from the feeling that he wasn’t trapped anymore.

—

Six months later, Aarav stood by the community hall entrance, nervously adjusting the corners of his display board. A banner above read: Local Lives: A Photo Walk Through Healing. His section had a small printed title in the corner: The Abyss Below.

He hadn’t told many people what it meant.

Photography had never been his career. He worked as a backend developer for a startup in Lower Parel—quiet hours of code, debug lines, headphones in. But after the panic attacks began, he couldn’t focus. He had taken medical leave, unsure if he’d return. With therapy and Ira’s support, he slowlyeased back into work—one day remote, one day in the office, then half-weeks. His manager had been surprisingly kind. “Mental health is health,” she had said. “Let us know what you need.”

He still worked there. Now on a flexible routine. And this—this photography—wasn’t a replacement. It was something else. Something that let him say what his voice often couldn’t.

His photo series stretched across the softboard. Shadows cast in narrow stairwells. A tea glass tipped over on a table. An old man sitting alone near a locked gate. Light falling through barred windows, making patterns that looked like cages but also like stained glass.

He hadn’t taken a single photo of faces. Only spaces. Emotions lived in corners too, he’d realized.

People walked around quietly, some pausing, some nodding. A few whispered.

Then a man stepped closer. Maybe in his sixties. Weathered face, white kurta, a lanyard from the event swinging from his neck. He studied the photo of the empty train platform—just a metal bench and scattered wrappers, the overhead wires cutting the sky.

“That one hit me hard,” the man said, voice low. “I used to be a conductor. Thirty years. Retired two years ago. Haven’t gone back since. Not once. But this… this made me feel like I did.”

Aarav swallowed. “It hit me too,” he said. “That was… the first time I stood there again.”

The man gave a slow nod, then walked away.

Ira joined him, holding two cups of coffee. “You okay?”

“I am,” he said. “Actually, I am.”

They walked back home through quiet lanes lined with bougainvillea. A gentle breeze picked up, carrying the scent of frying pakoras from a stall nearby. Familiar. Safe.

“So,” Ira nudged him, “what’s next?”

He looked up at the stars peeking out through the smog. “I was thinking of taking the train again. Maybe with my camera this time.”

Her face lit up. “And maybe later, teach that weekend workshop you once talked about?”

He raised an eyebrow. “You’re relentless.”

She grinned. “I’m your sister.”

He looked ahead, where the tracks would be humming with life, just a few streets away. “Yeah,” he said. “Maybe I will.”

—

The End

Leave a comment